The Patron of Print: The Reimagination & Democratisation of Art Collecting

“If you want to collect rather than simply buy in an ad hoc fashion you do need to be systematic, but take time to look around and think about what you like truly and deeply. [...] Go to the print fairs and talk to gallerists and artists”

Since 2001, Dr Mark Golder has worked closely with Pallant House Gallery to create a donated collection of over 500 prints, which grows every year with his generosity. We spoke to him about his approach to owning fine art, both the process and the meaning.

As a teacher, you don’t fit the imagined notion of a multi-millionaire art collector yet you have built one of the most impressive print collections in the UK. Starting from the beginning, how did you get into art collecting and what were your first purchases?

The seed for collecting was sown through exposure to the collecting habits of a particular family: the Barlows. A university friend’s grandfather had been a collector of Chinese and Turkish ceramics which he bequeathed to various galleries. Lying around the house were magazines of what is now called The Art Fund, and I read there about a bequest by another family member made through the Fund. I was just drawn to the idea of collecting and giving… but with the personal proviso that I never thought I would have the money to do it.

You’ve been described as a ‘collector’ rather than a ‘buyer’ - how would you distinguish between the two?

Language in the art world is very interesting. Museums and galleries have collections and they make acquisitions rather than buy things. I believe I started as a buyer, a print or ceramic here, a print or ceramic there. I would say that period in my life continued until I settled down with Brian in the late 1980s. I knew what I was going to do with my life (teach) and what I wanted to do with my hard earned dosh: collect and donate. I think ‘collecting’ suggests a degree of planned looking and reading, and the setting of some sort of goal.

What is it about Modern and Contemporary works that you are drawn to rather than the Old Masters?

It is not that I am not drawn to Old Master prints. Anybody who loves printmaking will almost certainly whisk themselves off to the nearest show of Dȕrer or Rembrandt, and I love reading the catalogues of print collectors who have concentrated on the Old Masters. I, however, want to make a commitment to the artists of my lifetime (so post-World War 2) to help them be seen and appreciated now. This is the work closest to us in time and spirit. It expresses the concerns and interests of people now (or not too far in the past).

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen, from The Apocalypse, 1498

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Artist's Mother: Head and Bust, Three-Quarters Right, 1628.

When working on a finite budget, how do you know what to choose? How do you personally define ‘value’ in art?

‘Value’ can be answered in a number of different ways. For me a work is valuable if it moves me in some way. This ‘movement’ can be a combination of aesthetic pleasure, intellectual stimulation, emotional stimulation, or art historical significance. As to monetary value, you do have to be careful. Even contemporary prints can be very differently priced by different gallerists. You need to do your research and talk to people you trust. Then buy what you can afford, but always remembering to go as high as you can for a really good example.

Where do you acquire your prints? Is it a case of huge amounts of research, or is it a spontaneous purchase?

It can be both. When I was in my 30s I tended to be more tentative. I can remember it took me thirty years to get round to buying something I first saw in the 1980s – so not much spontaneity there. Now I’m in my 60s I find myself going more with my gut reaction; so there are some prints we have which do not fit the main collection narrative. There are others which are the result of research. I recently bought a 1957 print by a Scottish woman artist which helped fill a gap in the prints we are buying for Pallant House in Chichester.

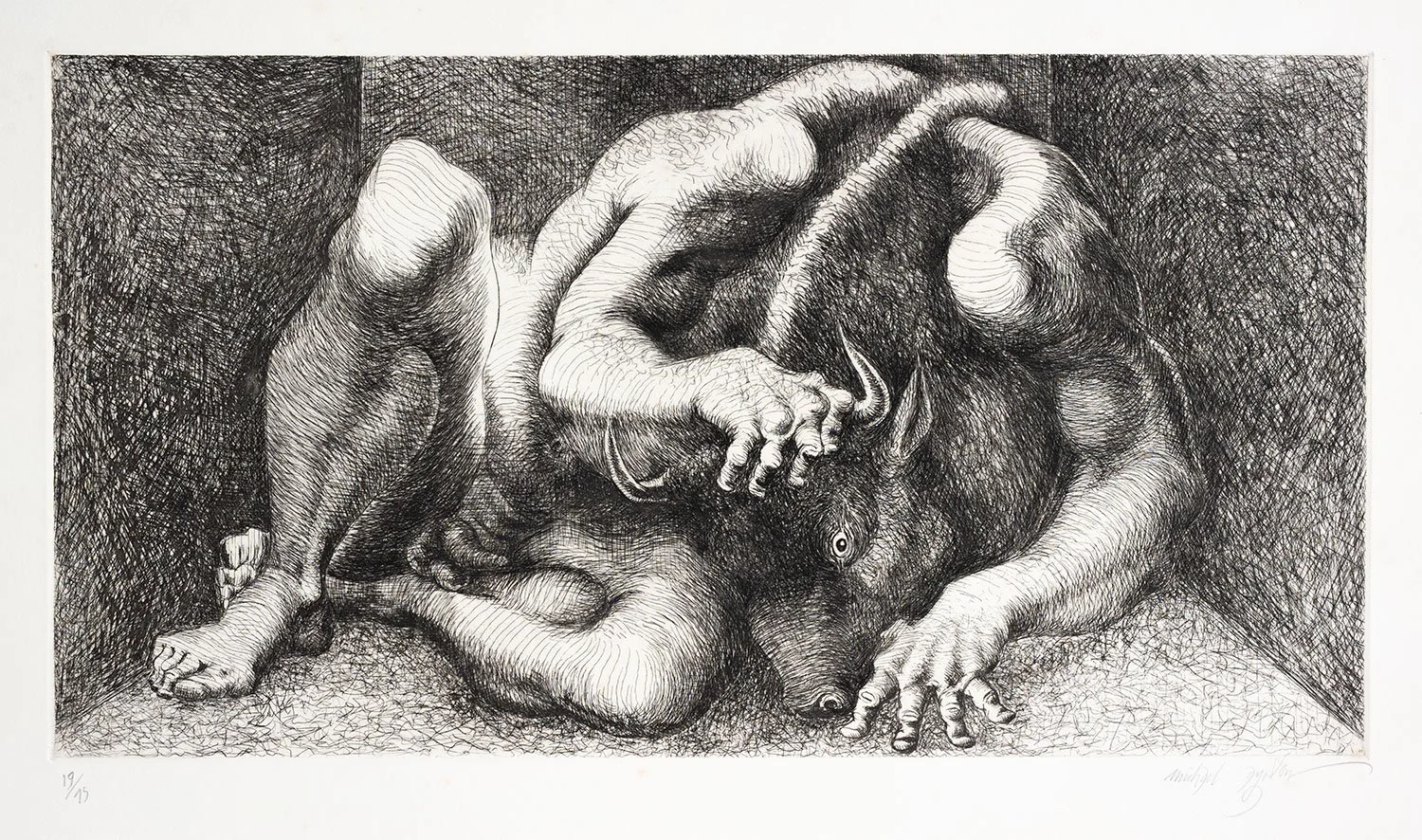

Michael Ayrton, Alone, 1971. Etching.

What role do emerging artists play in your art collection?

I am always on the lookout for artists who are new to me. This may mean that they are young artists: I recently purchased a print from Jake Garfield who was showing work at the Woolwich Print Fair in 2021. However, I also purchased in December work by someone else who had shown at Woolwich, a work by John Angus. I thought he was a young artist, only to discover he has been around quite some time, but working in a different area. For Pallant we are also interested in ensuring women artists get a good representation.

A Meeting of Earth and Aether [after Cr] (mud, silver, & yellow), 2019. Screenprint.

Jake Garfield, Man Painting a Picture, 2021.Woodcut & Lino.

You talk about print as a ‘democratic art form’. Of course, the lower price points through the nature of editioning can open things up to broader audiences. In what other ways do you find the medium as a more accessible art form?

The idea of print as a ‘democratic’ art form is borrowed from Colin St. John Wilson, the architect of the British Library, who bequeathed a considerable number of art works to Pallant House. By democratic he did mean that someone who could not afford a painting could afford something which came from the hand of an artist they admired. I find prints accessible because, unlike paint on canvas, they are ink on paper… and I am a book lover. I am drawn to the subtle effects artists can achieve by themselves or with the help of a printer.

Your model of collecting to share builds a wonderful sense of community: artists; print studios; galleries; visitors. How important is it for you to have this added depth of meaning in art ownership, and why? Does this affect your approach to collecting?

For me it is important because it is my form of outreach. I would see myself as an agnostic humanist who believes the world would be a better place if we could learn to share more, but that is rooted in a Christian upbringing which stressed thinking about others. I see no ‘merit’ in this. It is simply an aspect of my upbringing which ‘took’. I get pleasure from viewing prints, but I also get pleasure from seeing other people’s reactions and sometimes engaging them in conversation in order to tease out their responses.

Dean Walter Hussey inspired your philanthropic model of collecting and donating, and you will be currently inspiring others. Have you come across other philanthropists in your journey who you resonate with or have inspired your model in some way?

Not directly, apart from the Barlow model when we started. However, there are some people who have collected prints (and other works) who I do admire. Hamish Parker, a man with pockets many times deeper than ours, gave the British Museum £1,000,000 to buy Picasso’s ‘Vollard Suite’. Alexander Walker also gave a significant print collection to the same institution. You can read about him in ‘Living with art’. George and Ann Dannatt made a significant contribution to Pallant. Buy a copy of ‘St Ives and British Modernism’.

Can new collectors offer the same generosity, and if so how?

Of course they can, and I hope that they will. We often get told that our way of working with Pallant is unusual because we work with the director and acquisitions’ committee to create areas of collection and gap filling. That is, ours is not a bequest but an ongoing gift. I think more people in the USA would understand this model. Any young collectors can look around them to see where they might help a local or national collection. There is never enough public money for acquiring art. Look around for a gallery you can work with.

What would your advice be for aspiring collectors?

If you want to collect rather than simply buy in an ad hoc fashion you do need to be systematic, but take time to look around and think about what you like truly and deeply. I still have some prints in a plan chest which I put down to ‘learning experience’. Go to the print fairs and talk to gallerists and artists. I enjoy working closely with both. Brian constantly buys work by the Japanese artist Nana Shiomi, whom he met through the Rabley Gallery, because he loves her and her printmaking. Finally, do your research – build up a library!

Nana Shiomi, Putting Air Into the Picture. Letting Air Out of the Picture, 2019. Woodcut on Handmade Japanese Paper

What are the highlights of your personal collection?

That is quite hard to say because works are constantly coming and going. I would never give as a gift something which I would not personally have in the house. So Pallant’s ‘Hockney to Himid’ exhibition uses about 75 of the 500 prints we have donated. Amongst those Brian loves Paula Rego’s ‘Crumpled’ from 2002. I am drawn to the great carborundum triptych by Hughie O’Donoghue: ‘Three Studies for a Crucifixion II’ (2000). Both of us love anything by Ana Maria Pacheco, who shows with Pratt Contemporary Art.

Paula Rego, "Crumpled", 2001-02. Lithography on paper.

Ana Maria Pacheco, Perils of faith 4, 1990. Drypoint.

Hughie O'Donoghue, Three Studies of a Crucifixion, 2000. Carborundum etchings.

For a greater insight into The Golder-Thompson Gift at Pallant House, and to discover more about the generous philanthopists, Mark Golder and Brian Thompson, make sure to read the wonderfully comprehensive interview by Pallant House Curator, Louise Weller in the current catalogue for Hockney to Himid: 60 Years of British Printmaking.